PROTECTING THE LITTLE GUYS: INNOCEANA’S CATALOG OF INVERTEBRATES (INMOLO) IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC OF COSTA RICA

But what even are invertebrates? Well, their name is fairly descriptive of their identity. Invertebrates are animals without a backbone, or vertebrae. This morphological trait is applicable to animals such as corals, octopus, crabs, clams, sea snails, sea slugs, marine worms, and many more. Due to their size and abundance, many invertebrate species are at the base of food webs. This means that they are valuable sources of food for larger predators; essentially, their presence keeps larger animals alive! Without them, predators would have nothing to eat and would cease to exist themselves.

Additionally, many invertebrates possess really unique abilities and characteristics that can be interesting to study. For example, the nervous system of the octopus is extremely complex, as they have a central nervous system (or “brain”) in each of their 8 arms. The biological structure of these incredible creatures could be studied in more depth and may reveal groundbreaking discoveries. Some invertebrates even possess chemical compounds and unique microbiomes that can be useful in the field of medicine! Specifically, sea cucumbers have an incredible microbiome in their intestinal tracts, which could be extracted and possibly replicated so that we can use the same microbiota in probiotic medicine. And unfortunately, there are other species that are so poorly studied that we don’t know their ecological significance yet.

The lack of available information is why Innoceana started the INMOLO project in the first place. INMOLO stands for Invertebrates Monitoring and Location and involves collecting scientific data as a baseline for creating a book that catalogs all marine invertebrates found in the South Pacific of Costa Rica. This book’s purpose is to educate both the public and the scientific community on the invertebrates that are found in this region, as well as highlight their ecological significance. This also provides recognition for the contributors that worked on the book.

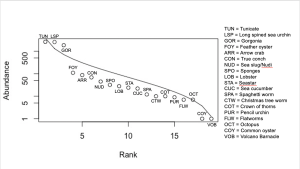

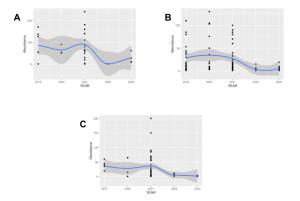

In addition to creating the book, the INMOLO project involves collecting data on the abundance and size of invertebrates in the South Pacific of Costa Rica. Specifically, data was collected at five dive sites off the coast of Caño Island and two sites off the coast of Parque Nacional Marino Ballena. For around five years, since the emancipation of Innoceana, the abundance and size of 25 indicator species were recorded along 30 m long transect lines. This form of random survey provided a picture of the overall invertebrate populations at the sites being sampled. Using this data, we are able to determine which species are most common and which have experienced a population decline in the South Pacific of Costa Rica.

Based on the data collected, the species with the highest abundance of individuals include tunicates, long-spined sea urchins, and gorgonias. Due to their higher frequency in our Costa Rican marine ecosystem, it was easier to examine the population growth trends for these three species in particular. Unfortunately, it was, in fact, evident that the populations of these species have declined over the past five years. The next step for the INMOLO project is to begin investigating why this is!