Tenerife's underwater treasures: exploring the island's corals

The crystal-clear waters surrounding Tenerife hide a treasure often unknown: corals.

These extraordinary organisms, true architects of the sea, create vital habitats for an incredible variety of marine species (Darling et al., 2017). While corals are commonly associated with tropical coral reefs, the coasts of Tenerife host a surprising diversity of corals.

In this article, we will guide you through the discovery of the island’s most fascinating coral species, exploring their ecological importance, the threats they face, and how to contribute to their protection.

Marine Conditions around Tenerife

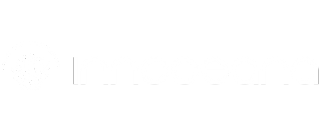

The waters surrounding Tenerife, part of the Canary Islands archipelago (Fig.1), are characterized by mild temperatures throughout the year, generally ranging between 18°C and 26°C (SeaTemperature.net, n.d.). The temperature varies across the island, with cooler waters in the north and warmer waters in the south. This difference in temperature helps support a wide variety of marine species (López et al., 2020). Although the waters are generally low in nutrients, occasional currents bring deeper, nutrient-rich waters to the surface (upwelling), nourishing marine life and creating ideal conditions for various species, including certain types of corals.

The most common coral species in Tenerife.

Corals are animals, and not all corals are the same. Some species establish a symbiotic relationship with dinoflagellate algae, often referred to as zooxanthellae, which live within coral cells and play a crucial role in their survival, particularly in tropical environments (Roth, 2014).

It is important to note that the waters around Tenerife do not host traditional tropical coral reefs, like those in the Red Sea or the Caribbean. The relatively lower temperatures and different environmental conditions limit the proliferation of reef-building corals (Mcllroy et al., 2019). However, soft coral species and some species of hard corals adapted to subtropical conditions can be found. Species that significantly contribute to the local marine biodiversity.

One of the most characteristic families in the waters around Tenerife is the Gorgoniidae, which includes species such as Leptogorgia ruberrima (Scarlet sea fan) and Leptogorgia viminalis (Yellow sea fan) (Fig.2). These soft corals, part of the octocorals group, have a flexible, protein-based internal skeleton , very different from the rigid calcium carbonate structure of hard corals. They primarily grow in deep, less illuminated waters, usually between 30 and 150 meters, but they can occasionally be found closer to the surface, away from human activities (Sánchez et al., 2019).

Their branched structure, reminiscent of a tree, provides internal support, but unlike hard corals, they do not form solid barriers. These vertical three-dimensional structures offer shelter, nourishment, and protection to numerous marine organisms, including fish, invertebrates, and other marine species.

Beyond their ecological importance, gorgonians are also the focus of scientific studies for their unique properties. Several research efforts have highlighted the potential of gorgonians in the field of medicine, thanks to their natural compounds with antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and antimicrobial properties (Kupfner & Hallock, 2020).

- Antipathozoanthus macaronesicus (Macaronesian anemone);

- Balanophyllia regia (Golden star coral);

- Dendrophyllia ramea (Tree coral);

- Phyllangia americana mouchezii (Dark colonial coral);

- Madracis asperula (Green reef coral) ;

- Leptogorgia ruberrima (Scarlet sea fan);

- Leptogorgia viminalis (Yellow sea fan);

- Anthipathella wollastoni (Black coral);

Figure 2. Gorgonians: Leptogorgia ruberrima (left) and Leptogorgia viminalis (right).

Source: REDPROMAR (https://redpromar.org).

Another important family in the waters of Tenerife is the Myriopathidae, which includes the species Antipathella wollastoni (Black coral) (Fig.3), also known as black coral. These corals are exclusively colonial and develop into branching formations that can resemble bushes or fans (Wagner et al., 2012). Antipatharians, or black corals, have a resilient and elastic internal skeleton that is black in color, hence the name, while externally they appear white due to the polyps that cover them (LifeGate, 2023). Although they are commonly considered azooxanthellate (meaning they do not host symbiotic algae), they can form dense aggregations, sometimes referred to as .

These black coral formations have a significant impact on the surrounding environment, altering local conditions and creating true biodiversity hotspots (Moccia et al., 2022). They can be found at a wide range of depths, from coastal waters to deeper marine areas, hosting a variety of marine species (Gouveia et al., 2023)

Figure 3. Black coral (Antipathella wollastoni).

Source: Innoceana

Curiosity

In 2008, the hydrocoral Millepora sp. (Fig.4), commonly known as “fire coral”, made its first appearance in Tenerife, sparking curiosity among researchers. This marine organism, known for its ability to build coral reefs, is not native to the Canary Islands, as it comes from tropical waters. Its presence demonstrates how marine dynamics are shifting: climate change is facilitating the arrival and proliferation of exotic species, such as tropical ones, even in subtropical environments.

The hydrozoans of the Millepora genus are found throughout the circumtropical region (the areas surrounding the tropical zone), living in shallow waters where they form colonies capable of profoundly altering the surrounding environment. In Tenerife, they can be found at depths of 6-8 meters on rocky seabeds, in a few isolated locations where, despite their limited spread along the coast, they seem to thrive.

The Canary Islands seem to have favorable weather conditions that support the development of these tropical colonies. While Millepora sp.’s distribution is still restricted, water temperatures could soon offer the perfect environment for their expansion.

Over the past 20 years, the islands have experienced an average temperature rise of about 1°C, a change that hasn’t gone unnoticed (Martín et al., 2012).

Figure 4. Millepora sp. in Tenerife’s shallow waters.

Source: Innoceana

Threats

The corals of Tenerife play a crucial role in marine biodiversity, but they are increasingly exposed to specific threats that compromise their health and survival. Here are some of the most pressing challenges:

- Pollution

Chemicals, plastics, and other waste accumulate in the oceans, causing devastating damage to corals. These materials not only compromise their structure but also disrupt the balance of marine ecosystems that depend on them (Akhtar et al., 2022).

2.Unregulated tourism

Oil and gas exploration, seabed extraction, and cable laying can crush corals, alter currents and nutrient flows, and release toxic drilling muds that smother and kill corals and other marine organisms (Roberts & Hirshfield, 2004).

3.Unregulated tourism

Tourist activities such as indiscriminate anchoring and direct contact with corals during diving or snorkelling can cause physical damage to these delicate structures, compromising their integrity and ability to regenerate.

Conclusion

Protecting corals and marine biodiversity requires small yet significant actions from everyone. It is important to avoid touching or collecting corals and other marine life, as even minimal contact can harm these fragile organisms. It is essential to always follow the guidelines set by local authorities and tour operators to minimize environmental impact.

Responsible discovery of corals can be achieved by participating in activities managed by operators who adopt sustainable practices. Every action counts: supporting conservation initiatives, respecting the environment, and promoting eco-friendly behaviours are crucial steps in ensuring the protection of these ecosystems.

Bibliography

Akhtar, R., Sirwal, M.Y., Hussain, K., Dar, M.A., Shahnawaz, M., Daochen, Z. (2022). Impact of Plastic Waste on the Coral Reefs: An Overview. In: Shahnawaz, M., Sangale, M.K., Daochen, Z., Ade, A.B. (eds) Impact of Plastic Waste on the Marine Biota. Springer, Singapore.

Clemente, S., Rodríguez, A., Brito, A. et al. (2011). On the occurrence of the hydrocoral Millepora (Hydrozoa: Milleporidae) in the subtropical eastern Atlantic (Canary Islands): is the colonization related to climatic events?. Coral Reefs 30, 237–240.

Darling, E.S., Graham, N.A.J., Januchowski-Hartley, F.A. et al. (2017). Relationships between structural complexity, coral traits, and reef fish assemblages. Coral Reefs 36, 561–575.

Gouveia, A., Godefroid, M., Dubois, P. et al. (2023). Thermal stress response of Antipathella wollastoni (Gray, 1857) from the Canary Islands archipelago. Coral Reefs 42, 1263–1269.

Kupfner, J. S., Hallock, P. (2020). A review of symbiotic gorgonian research in the western Atlantic and Caribbean with recommendations for future work. Coral Reefs 39, 239–258.

LifeGate (2023). The discovery of black coral in Marettimo, as told in the documentary ‘Il bianco nel blu, from https://www.lifegate.it/corallo-nero-marettimo-documentario

López, C., Moreno, S., Brito, A., & Clemente, S. (2020). Distribution of zooxanthellate zoantharians in the Canary Islands: potential indicators of ocean warming. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 233, 106519.

Mcllroy, S.E., Thompson, P.D., Yuan, F.L., Bonebrake, T.C. and Baker, D.M. (2019). Subtropical thermal variation supports persistence of corals but limits productivity of coral reefs. Proc. R. Soc. B, 286.

Martín, J.L., Bethencourt, J. & Cuevas-Agulló, E. (2012). Assessment of global warming on the island of Tenerife, Canary Islands (Spain). Trends in minimum, maximum and mean temperatures since 1944. Climatic Change 114, 343–355.

Moccia, D., Carugati, L., Follesa, M. C., Cannas, R., Carbonara, P., Pusceddu, A., & Cau, A. (2022). Environmental Status and Geomorphological Characterisation of Seven Black Coral Forests on the Sardinian Continental Shelf (NW Mediterranean Sea). Biology, 11(5), 732.

Roberts, S., & Hirshfield, M. (2004). Deep‐sea corals: out of sight, but no longer out of mind. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2(3), 123-130.

Roth, M. S. (2014). The engine of the reef: photobiology of the coral–algal symbiosis. Frontiers in microbiology, 5, 422.

Sánchez, J.A. et al. (2019). Gorgonian Corals. In: Loya, Y., Puglise, K., Bridge, T. (eds) Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems. Coral Reefs of the World, vol 12. Springer, Cham.

SeaTemperature.net. (n.d.). Current sea temperature in Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. SeaTemperature.net, from https://it.seatemperature.net/current/spain/tenerife-canary-islands-spain.

Wagner, D, Luck, D.G, Toonen, R.J. (2012). Chapter Two – The Biology and Ecology of Black Corals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Hexacorallia: Antipatharia). Advances in Marine Biology, Academic Press 63, 67-132.